United we stand: Strengthening the liquidity ecosystem

Robust and well-supported liquidity ecosystems keep the commercial world turning, whatever else is going on in society at large. But it’s the symbiotic relationship between bank and corporate that keeps those systems strong. Edwin Hartog, Head of GTB, Societe Generale, Netherlands, and Joost Bergen, Founder of liquidity management advisory and training firm Cash Dynamics, explore the nature of this true partnership.

In addition to the challenges of dealing with tight-liquidity-markets and the quest for solutions to manage and protecting systems that were not meant to work remotely, the gradual recovery from the pandemic has been disrupted by the fast emergence of more severe trading conditions.

Hugely increased political tensions, high inflation and interest rates, energy cost-of-operations and cost-of-living crises have all severely hampered recovery for many businesses. The perception of risk has increased considerably. And now, alongside serious ongoing discussions around measures that can be taken to protect margins, business continuity, and global sustainability – or ESG – can no longer be ignored.

For all of these issues, treasury is on the front line. And with liquidity still an issue for many, the question of how to manage refinancing and the efficient recycling of liquidity, has become more relevant than ever.

Cash flow forecast is Queen

“Depending on the individual business, its sector and size, more firms are now exploring their options for liquidity buffers to safeguard their continuity in the face of unprecedented conditions, or black swan events,” observes Bergen. “This increases the relevancy of the treasury function, and the continuous recalibration of treasury operations and its policies to this new reality.”

For Hartog, with post-pandemic default ways of doing business having changed, companies suddenly find themselves “in a completely different environment”. For example, it’s one in which banks, driven by unavoidable sustainability issues, “have swapped their previous enthusiasm to finance business-as-usual for an eagerness to finance the transition to net zero”.

Combined with the general rise in cost of capital, Hartog believes that from boardroom to treasury, companies are more focused on their cash-generating capacity and daily cash positions. “And that brings the liquidity discussion to a whole new level.”

The emergence of liquidity as a “scarce asset that needs to be managed as such” is, for Bergen, the root cause of why there is now greater attention on cash flow forecasting, and in the reporting of cash at board level. The understanding is that the more cash that is available, the more the business can absorb economic shocks and/ or Black Swans, and the more a business can recycle its own liquidity, the less it has to rely on external sources. This, he declares, is raising the stakes for three key treasury matters: the visibility, centralisation, and investment of cash.

“Now there’s more sense of urgency than before,” he notes. With the feeling that we have not seen the last of so-called black swan events, he cautions that with liquidity markets clearly subject to massive disruption too, “your own liquidity is probably the only way to come through these moments”.

If cash has reconfirmed its status as king, “then probably the cash flow forecast is queen”, suggests Bergen. With technology continuing to enable progress in forecasting accuracy for those that use it, Hartog adds that the resulting insight provides vital flexibility of that liquidity.

Hartog also believes companies are looking to find the right balance and accessibility for their cash buffers, with many “very alert” to the possibility of needing it sooner rather than later. Of course, this brings the conversation back to the three pillars of cash visibility, centralisation, and optimal investment.

In the first instance, cash visibility, Hartog draws a distinction between simple awareness of where the cash is and in also having control over that cash – a situation that may look somewhat different where trapped cash is unavoidable. This brings to the fore the second notion of centralisation. Indeed, he notes, while many blue-chip businesses already had cash-pooling arrangements before current disruptions, there is far more interest now for this set-up from smaller firms.

Hartog admits: “It’s an interesting challenge for banks now. We need to provide corporate clients with a structure that offers them full visibility and control over their cash, and which enables them to avoid the unnecessary costs of debt.

Balancing the books

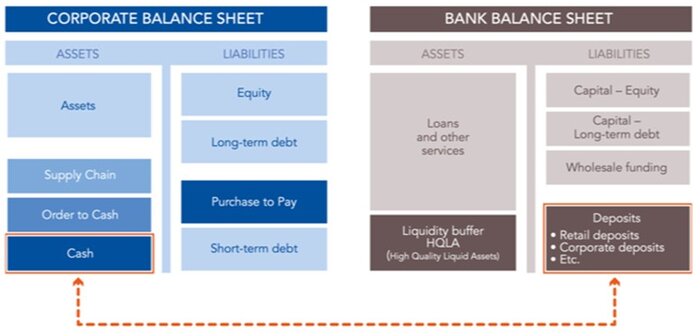

As moderator of a liquidity management working group for the Euro Banking Association (EBA), Bergen has an abiding interest in the corporate liquidity landscape. He describes that structure as an “ecosystem”. This is best depicted in the following graphic (fig. 1).

Fig. 1 (source EBA)

On the blue side of the graphic, what is being shown is the working capital cycle of corporates. They require access to the banking system’s payment infrastructure, and a host of other banking services (including trade finance, FX, and lending), to ensure this process is maintained.

Eventually every payment in that cycle becomes a cash item on the corporate balance sheet. This is typically deposited on a bank account noted as an entry on that bank’s balance sheet (as shown on the brown side of the graphic). It follows that the greater the level of corporate cash deposits, the more banks are able to fund their own balance-sheet activities, such as lending.

As already established, to be able to absorb financial shocks more effectively, corporates need a strong cash balance. But achieving this requires visibility over their cash and liquidity. Banks have a natural interest in guiding corporate clients towards improved visibility and accessibility to acquire those corporate cash deposits.

In practice, it’s solutions such as cash pooling and cash concertation, and virtual account structures that develops that idea, which offer corporates greatest insight and direct accessibility to their available liquidity across locations and currencies. However, not all companies use these solutions yet, and so the question arises do they really know their cash position only at end of month or end of quarter on a management accounting basis, notes Bergen. “Many do not know where their buckets of cash really are on a daily basis, or even how many accounts they have globally and with which banks. This is why they often find themselves fully drawn on their RCFs – as in an accounting report there can be multiple buckets of liquidity - they simply do not have sufficient visibility over their cash.” and as a consequence have opposite positions.

On the banking side of the equation, while there is a natural ebb and flow of deposits, the overall sum on the balance sheet needs to remain consistently at a high level because banks use this total to measure and manage their balance sheet and financial objectives. But they also must comply with stringent regulatory requirements for capital adequacy, with Basel’s protective liquidity buffers ensuring the wider banking system can withstand stress from a liquidity perspective.

With the ecosystem finely balanced, the nature of the relationship is clear to Bergen: “Banks and corporates need each other”. For banks to achieve their funding, many have a retail franchise supporting this need.

Balancing the relationship

With companies increasingly driven to evaluate their cash management landscapes, many are looking at the number of banks and accounts they have, notes Hartog. And banks, too, are reconsidering the true value of their client relationships. In these days of increasing cost of compliance (KYC/monitoring) every single account is judged upon its own cost income ratio.

“When a bank is serving only one country with some ancillary business, and the operational flows go elsewhere, it’s not really viable to remain part of that ecosystem,” he explains. “What banks are interested in is stable, long-term operational flows.”

There is a message here for treasurers managing their bank relations globally, says Bergen, and that is the need to understand the interdependency within that relationship, “and how you divide your total bank wallet between your banking partners”.

Of course, this is a two-way flow. By bringing its operational balances to the bank, in return, the client can optimise its liquidity by accessing the bank’s technologies, expertise, and its balance sheet. “A product such as cash pooling is a classic demonstration of how we are there for the client and how they are there for us,” emphasises Hartog.

A previous published case study with a Societe Generale client reveals how the implementation of a bespoke virtual account pooling structure enabled faster collections and reconciliation. By significantly reducing the need to go to the market for funding for day-to-day operations, not only were substantial cost savings made but also Hartog reveals that it, along with other factors, ultimately even had a positive effect on the company’s credit rating in being able to reduce their debt position.

“It is important for our client because it has clearly improved their financial performance. But it is also interesting for us as a bank to demonstrate our capability to enhance a company’s liquidity strategy in providing it with a dedicated suite of solutions. This is the level of discussion we want to have with all clients.”

This exchange, based around adding value rather than focusing on isolated products and services, is even shifting how core products are being approached. Where once financing and cash management were two different activities, “today they are one and the same”, notes Bergen. “You cannot have an RCF (revolving credit facility) if you don’t understand your cash flow dynamics. The solutions banks can provide nowadays offer companies crucial visibility and insight.”

Maintaining value

Having moved from years of low-to-negative rates, companies are now operating in an environment where inflation and interest rates have risen rapidly.

Another effect, Bergen notes, is the change of payment behaviour and the extension of payment dates, impacting the firm’s liquidity position. This is detrimental across the value chain. Working capital investments, for example, particularly by smaller companies, have been curtailed quite severely.

Value chains are created by a functioning interdependency between small and large companies, and banks are a key part of that ecosystem, notes Bergen. “We should not be battling against each other, but instead working together, and reducing the total capital employed in value chains, because then we all benefit.”

Banks clearly see opportunities to assist here, comments Hartog. “In terms of supporting value chains in uncertain times, it’s not only about processing payments and receivables, but it’s also around finance. We are seeing increased demand to expand or originate new deals in areas such as supply chain finance.”

Among the economic challenges, and perhaps surprising level of interdependence in the value chain, there is a simple message for all stakeholders, conclude Bergen and Hartog. “The focus on liquidity efficiency should be even more on the agenda than in the past for both banks and corporates. Especially on the corporate side, visibility and centralisation of cash drives working capital improvements which positively impacts the costs of funding. And that goes a long way to ensuring the whole ecosystem is stronger and better prepared to weather new black swan events.”

This article is part of the whitepaper "Shaping the Future of Treasury", published by Treasury Management International (TMI) - September 2024. Click here to download the whitepaper.